The Nobel Prize in literature was given to French novelist Annie Ernaux on Thursday for her work that uncovers obscure aspects of memory, family, and society. Annie Ernaux has used her history to analyze life in France since the 1940s.

The highly intimate experiences and emotions—love, sex, abortion, shame—examined in Ernaux’s autobiographical works are set within a shifting web of social and class relationships. Her upbringing in a working-class family in the northwest French area of Normandy served as the basis for most of her writing.

Ernaux, 82, was honored for her writing’s “courage and clinical clarity,” according to the Swedish Academy.

The chairman of the Nobel literature committee, Anders Olsson, described Ernaux as “an extraordinarily honest writer who is not hesitant to address the hard truths.”

“She talks about topics that are taboo for other writers, such as her abortion, her resentment, her experiences as a lover who was dumped, etc. I mean, truly trying circumstances,” he stated in Stockholm during the medal presentation. And she uses straightforward and compelling words to describe these encounters. Although they are short books, they are quite powerful.

Ernaux is the first French Nobel laureate since Patrick Modiano in 2014 and is just the 17th woman among the 119 recipients of the award. She was one of France’s most celebrated writers and a leading feminist, and when a Swedish journalist called to congratulate her on the honor, she exhibited surprise and asked, “Are you sure?”

She told the TT news agency, “I was working this morning and the phone has been ringing all the time but I haven’t responded.” Ernaux said the award was “a great honor” and “a very great responsibility” to Swedish broadcaster SVT. In place of the word “fiction writer,” Olsson said Ernaux had substituted “an ethnologist of herself.”

Her more than 20 novels, the majority of which are rather brief, detail incidents in both her life and the lives of others around her. They provide unflinching depictions of her sexual encounters, abortion, sickness, and her parents’ deaths.

Olsson claims that Ernaux’s writing is frequently “scraped clean in plain language.” Ernaux refers to her writing as “flat writing” to paint a very objective picture of the events she is a retelling, absent of lyrical description or overpowering emotions.

Ernaux had a career as a teacher before she turned to writing full-time. Cleaned Out, her debut novel, came out in 1974. What They Say Goes and The Frozen Woman were the next two autobiographical books she wrote before switching to more overtly autobiographical pieces.

She writes: “No poetic reminiscences, no triumphal displays of sarcasm.” in the 1983 book La Place (A Man’s Place), which is about her relationship with her father. It comes easy to her to write in this objective manner.

While the 1997 book Shame examined a childhood tragedy, the 2000 film “Happening” shows an illegal abortion.

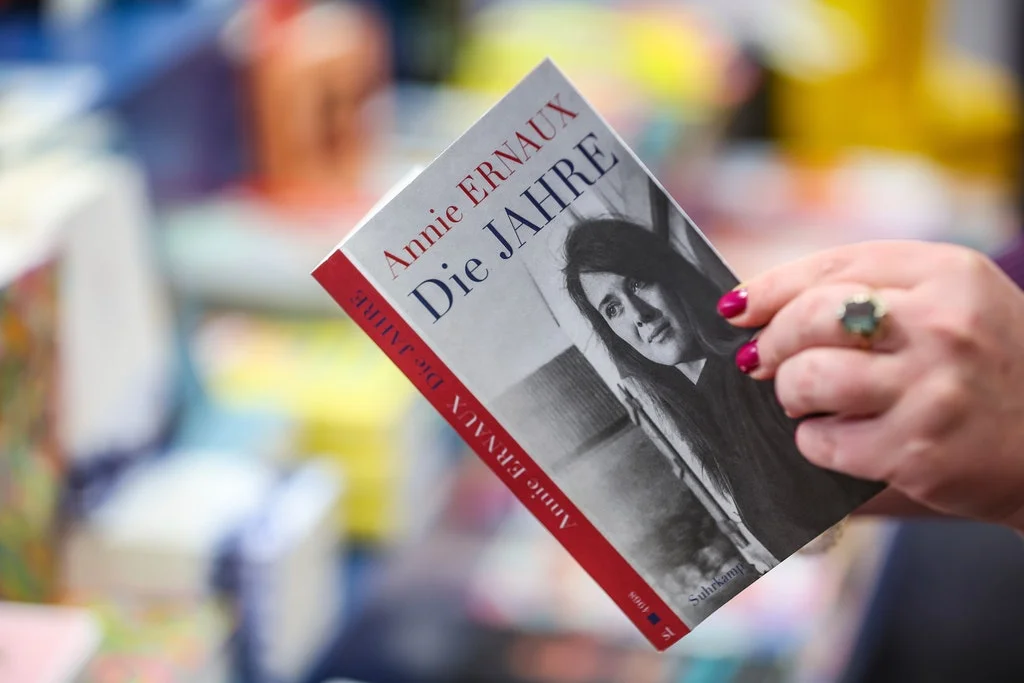

Her 2008 book The Years, which explored herself and broader French culture from the conclusion of World War II to the twenty-first century, received the most favorable reviews. In contrast to her other writings, Ernaux wrote in the third person in The Years, referring to her character as “she” rather than “I.” According to Olsson, the book has received awards and prizes and has been called “the first collective autobiography.”

The 2016 film “A Girl’s Story” chronicles the 1950s adulthood of a young woman.

It has long been argued that the Nobel Prize in Literature favors writers from Europe and North America too much and is majority male. Only the sixth Nobel literature laureate born in Africa, Tanzanian-born writer Abdulrazak Gurnah, took home the award last year.

Olsson continued, “Our focus must be on literary excellence, but we want to expand the purview of the Nobel Prize first and foremost.

Thanks to the prizes given to Gurnah in 2021 and American poet Louise Glück in 2020, the literature prize has been able to move past years of controversy and scandal.

The Nobel literature committee, which is named by the Swedish Academy, was shaken by abuse charges in 2018, which led to a member exodus, and the award was postponed. The academy restructured itself but received more criticism for awarding the 2019 literary prize to Austria’s Peter Handke, who has been dubbed an apologist for Serbian war crimes.

Svante Paabo, a Swedish scientist, won the Nobel Prize in medicine on Monday. Paabo discovered hidden information in Neanderthal DNA that was essential to understanding our immune system.

The physics award was shared by three experts on Tuesday. The concept of quantum entanglement, which may be utilized for specialized computing and to encrypt information, was first shown by the scientists Alain Aspect of France, John F. Clauser of the United States, and Anton Zeilinger of Austria.

The American scientists Carolyn R. Bertozzi and K. Barry Sharpless, as well as the Danish researcher Morten Meldal, were given the Nobel Prize in chemistry on Wednesday for creating a method of “snapping molecules together” that can be used to explore cells, map DNA, and create drugs that can more precisely target diseases like cancer. Ben Bernanke is one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize in economics.

On December 10, the winners of the prizes will receive cash awards totaling 10 million Swedish kronor, or almost $900,000. Alfred Nobel, a Swedish inventor who founded the award, made a bequest in 1895 that provided the funding.